The Renewing America Interview: Bill Bradley on Leadership and U.S. Tax Reform

September 12, 2013 10:59 am (EST)

- Post

- Blog posts represent the views of CFR fellows and staff and not those of CFR, which takes no institutional positions.

More on:

Months of relative calm on the U.S. fiscal front are set to end this month as Congress returns from summer recess, staring down the barrel of a possible government shutdown on October 1 (start of FY 2014), and another likely debt-limit fight shortly thereafter.

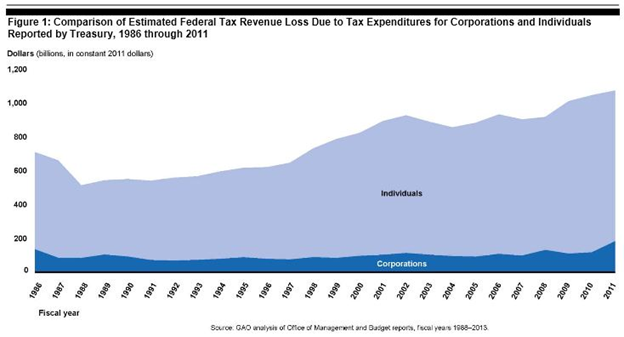

Amid the mounting budget debate, many fiscal policy experts have called for a total rewrite of U.S. tax law akin to what last occurred 27 years ago. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA 1986) overhauled a code riddled with special exemptions and credits (tax expenditures for individuals and corporations) that made the system overly complex, less equitable, and less efficient. Much like today, there was a desire among many policymakers to rehabilitate the way the country brings in revenue to boost growth and entrepreneurship, and improve fairness.

Leading the charge for tax reform in the early 1980’s, oddly enough, was a former basketball star-turned senator, who developed antipathy for the complexities of the federal tax code as a top earner in the NBA. Three decades on, Bill Bradley, in a recent CFR interview, was just as passionate about the need for fundamental tax reform, and he highlighted some important lessons from his experience.

(Federal revenue losses from corporate and individual tax expenditures fell after the 1986 reforms, but have risen steadily in the decades since, as shown in Figure 1.)

“There are four things necessary if you are going to have a shot at doing income tax reform today,” he told me. “One, you need a committed president; two, a committed Treasury secretary; three, a chairman of the [House] Ways and Means Committee and a chairman of the [Senate] Finance Committee who see their own political interests served by passing reform. And four, which is debatable, you need some zealot talking about tax reform all the time. Thirty years ago, that was me,” he said.

Bradley, now a Managing Director of Allen & Company LLC and a member of the board of directors of Starbucks Company, says tax reform was his top priority when he came to the Senate in 1979. Indeed, in many ways, the then 39-year-old New Jersey lawmaker laid the foundation for the ’86 overhaul with his Fair Tax Act of 1982 (co-sponsored with then Rep. Dick Gephardt), which sought to simplify the code, lower top rates and cull distortive tax breaks. Although the legislation died in committee along with thousands of other bills in the 97th Congress, journalists of the day were keen to acknowledge its seminal contribution to TRA 1986 and the dogged leadership of its author.

In Showdown at Gucci Gulch, the definitive postmortem of the politicking behind TRA 1986, Al Hunt, then Washington bureau chief at the Wall Street Journal, writes in the introduction: “At every critical juncture Bradley stepped in to provide an important push; rarely has a legislator with no formal leadership role or committee chairmanship played such an instrumental role in a major piece of legislation.” (“Gucci Gulch” was the name given to the hallway outside the Senate Finance Committee, where leading tax lobbyists in “expensive Italian shoes” plied their trade.)

Bradley says that there were a few simple, but significant principles that helped guide both parties in the 1986 effort: one, equal income should pay equal tax (i.e. loopholes should go); two, the market is a better allocator of resources than Congress (i.e. taxation shouldn’t bias investment choices); and three, those who have more should pay more.

While he was careful to stress that the policy negotiations in those days could have collapsed (and nearly did) at any time, Bradley said that the overarching principles outlined above provided a lodestar to the legislative process. “There was something in there for both Democrats and Republicans,” he said. “Republicans wanted lower rates and Democrats wanted fewer loopholes. And there was an agreement that together we could get both.”

A problem with modern reform efforts, says Bradley, is the lack thus far of a highly detailed plan put forth by tax legislators or the president, who both often speak broadly and vaguely about the issue. “If you are serious about getting it done, there is no substitute for a very specific proposal; I did it in ’82, I did another one in ’84 and ’85; [president] Reagan did one in late ’84, and another in mid ’85, and then we were off to the races because the president and the legislature had put out exactly what they mean about tax reform,” he said.

Leadership and buy-in from the White House was essential to the success of TRA 1986, Bradley said. “Reagan bought into it because when he was an actor the [top marginal income tax] rates were 90 percent. I bought into because when I was playing basketball, I was a depreciable asset. There were mutualities there that could be achieved only by agreeing.”

Today, however, the political calculus may be different. Sen. Max Baucus (D-MT), chairman of the Finance Committee—who along with Rep. Dave Camp (R-MI), chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, have been whistle-stopping the country pushing comprehensive tax reform—has often tried to downplay the role of the White House, fearing President Obama’s public support could stoke opposition in the Republican-controlled House.

Still, others intimately involved in the success of 1986 like Bradley say the president should be more out front in the proposal process. “If you’re going to ask people to walk the plank with you on important issues, and the president is just waiting to see what you produce, they’re not going to be willing to do it,” Bob Packwood (R-OR), who led the Senate Finance Committee when it unanimously passed TRA 1986, told Politico in July.

Of late, a central question dividing the parties on this issue has been whether dollars generated from eliminating tax expenditures will all be used to bring down rates—a revenue-neutral approach—or whether a portion will be used for new fiscal stimulus and/or deficit reduction. To the chagrin of many Republicans, President Obama proposed using corporate tax reform to do the latter in late July, despite the administration’s past support for revenue-neutrality.

Meanwhile, Baucus and Camp, who have created a bipartisan website to solicit reform ideas, plan to put forward their respective proposals (for corporate and individual taxes) in the coming weeks. But most analysts say the march toward a 1986-like fundamental rewrite of the code in the next sixteen months is decidedly uphill. (In January 2015, Baucus will retire and Camp will lose his chairmanship [term limits.])

Looking ahead, Bradley sees an opportunity for both sides to compromise by eliminating expenditures straightaway, but bringing down rates only as per capita income rises. “The idea is a rising tide lifts all boats. You close the loopholes immediately and use the money for deficit reduction, infrastructure and education. And then you say, for instance, if per capita income grows 2 percent per year, the [top marginal income tax] rate can go from 39.6 to 38. If it grows to 3, you get down to 37, until it’s back to 35 percent. That way you have both parties able to get what they want: lower rates, growing middle class income and targeted spending and deficit reduction.”

More Renewing America Interviews can be found here.

More on:

Online Store

Online Store